There’s a profound sense of home inside the Normandy, your starship throughout the Mass Effect trilogy.

A similar feeling is found in Dark Souls II’s Majula, your campsite in Dragon Age: Origins, or, hell, the entire province of Skyrim from The Elder Scrolls V. There’s something special about a player home or hub that makes you feel welcome and grounded in a fictional world.

But that’s not what makes Mass Effect – or any of those games – great. Not really.

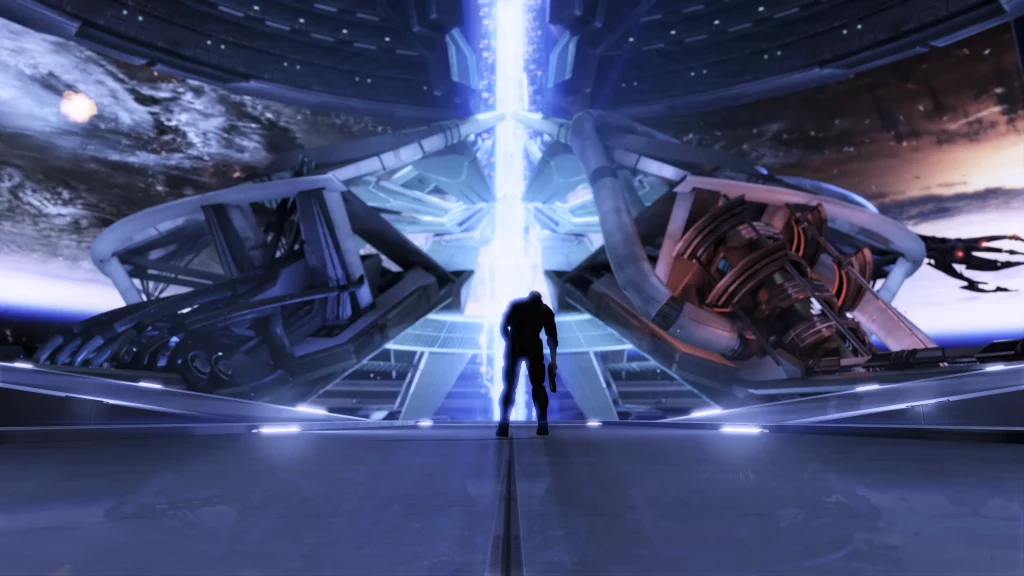

I just beat Mass Effect 1, 2, and 3 in sequence. Honestly, it is going to be hard to pick up another RPG soon because this series was so good. The world, the story, the characters, all of it.

An Understanding of Player Choice

It feels too easy or broad to say that Mass Effect is made incredible by all of its qualities – even if that’s the truth. I think it’s primarily Mass Effect’s implementation of player choice that makes it an experience seldom offered by other games. Putting aside all else, the games are a series of nuanced, difficult decisions that spark reflection in the player. I can’t count how many times I’ve made a split-second decision with the game’s Paragon/Renegade system, only to be left wondering if I made the right call.

Mass Effect supports a rather unique save importing feature – allowing you to maintain the decisions you made in the previous titles when progressing to the next game – adding a deeper level of weight and permanency to your actions. After all, what does freedom of choice in gaming really mean if there are no consequences?

During my playthrough of Mass Effect, I was reminded of the comments made by several major gaming outlets regarding developer BioWare’s latest title, Dragon Age: The Veilguard. A “return to form” for BioWare is how it was described by many. While I don’t think that’s necessarily true, there are certainly similarities.

The Veilguard features a clear attempt to present player freedom in the way that Mass Effect and the earlier Dragon Age titles did, but most of the choices come across as inconsequential or fail to invoke that same feeling of reflection.

Now, it’s important to mention that I really liked Dragon Age: The Veilguard. The game has its flaws, but the criticisms are exaggerated. I found myself happily lost in the gorgeous environments and satisfying combat. BioWare is still capable of writing endearing characters that you grow to love, too, but they don’t explore them to the same degree as their previous titles.

It wasn’t perfect, but it was fun.

This leads to an interesting conversation: is player choice a necessary component for a role-playing game?

What Mass Effect Got Right

I get it, there’s a difference between enjoying something and it being objectively “good”, but let’s return to Mass Effect for a minute. When we specifically focus on Mass Effect’s implementation of player choice, there is a great deal of agency handed to the player. BioWare placed trust in its audience to curate their own tale for the player character, culminating in the destruction or salvation of the galaxy – with room for nuance and interpretation.

Mass Effect indulges this freedom, so much so that the identity of the series is defined by its ability to let you take the lead on the story. Personally, I rely on this kind of freedom to immerse myself. It adds a level of interaction with the game that makes the story feel like it’s mine instead of the studio’s or developer’s. For this reason, Mass Effect is precisely what I want to see in an RPG.

Structured Storytelling

The Veilguard provides a more curated, linear narrative. The game is structured in typical BioWare fashion, offering dialogue options that allow you to respond in different ways and tones, but the world and characters tend to remain static outside of a handful of major events. There are a couple of major choices that will affect your companions and the story, but most of the game will funnel into the same outcomes and circumstances, regardless of the choices you make in dialogue.

From a gameplay perspective, this means the game is less varied from one playthrough to the next. The dialogue options do provide the necessary room to shape the personality for your character, but freedom of choice is a far smaller aspect of the game.

That is not to say that the quality of the story is necessarily worse than that of the Mass Effect trilogy (there may be other reasons, but some of the best stories offer little to no player freedom). It only means the story is less yours, and more what the developers believed it should be. You are less an active participant, and more a spectator.

Freedom in RPGs

At the core of storytelling, providing the consumer with the means to control a story’s direction is not essential to the story itself. However, in the context of RPGs, there are some additional considerations that need to be made.

Freedom of choice is a vehicle for the player to feel control over their actions and have more agency in what is happening in the game. A role-playing game’s ultimate goal is to immerse the player, to make the audience feel like they are part of the fictional world. I strongly feel that this kind of freedom is necessary for an RPG to succeed. This could explain why Dragon Age: The Veilguard may not be the perfect role-playing game, but is still an enjoyable experience nonetheless. In this way, Mass Effect and The Veilguard are almost incomparable, as the games are achieving different storytelling styles – despite what the marketing and major outlets may have suggested.

It is worth noting that we all engage with art in different ways. Role-playing games in particular can be deeply personal experiences by nature. Whether or not player choice is important to you is strictly your business. Assign value to the elements of gameplay that are important to you, and play with those in mind.